- Home

- Gary Corby

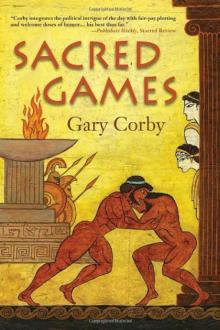

Sacred Games

Sacred Games Read online

ALSO BY GARY CORBY

The Pericles Commission

The Ionia Sanction

Copyright © 2013 Gary Corby

All rights reserved.

First published in the United States in 2013

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Corby, Gary.

Sacred games / by Gary Corby.

p cm

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-61695-228-0

1. Nicolaos (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Private investigators—Fiction. 3. Diotima (Legendary character)—Fiction. 4. Olympic games (Ancient)—Fiction. 5. Pancratium—Fiction. 6. Murder—Investigation—Fiction. 7. Athens (Greece)—Fiction. 8. Greece—History—Athenian supremacy, 479–431 B.C.—Fiction. I. Title.

PR9619.4.C665S23 2013

823′.92—dc23 2012046373

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Map illustration by Katherine Grames

v3.1

For Megan, Catriona and Helen

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

A Note On Names

Map

The Actors

Day 1 of the 80th Olympiad of the Sacred Games

Day 2 of the 80th Olympiad of the Sacred Games

Day 3 of the 80th Olympiad of the Sacred Games

Day 4 of the 80th Olympiad of the Sacred Games

Day 5 of the 80th Olympiad of the Sacred Games

Author’s Note

Events and Winners of the 460 BC Olympics

Glossary

Acknowledgments

In Praise of Timodemus

So as the bards begin their verse

With hymns to the Olympian Zeus,

So has this hero laid the claim

To conquest in the Sacred Games.

The Second Nemean Ode of Pindar, dedicated to

Timodemus, son of Timonous, of the deme Archarnae of Athens

A NOTE ON NAMES

MOST MODERN WESTERN names come from the Bible, a book which had yet to be written when my hero Nico walked the muddy paths of Olympia. Quite a few people have asked me what’s the “right” way to say the ancient names in these stories. There is no right way! I hope you’ll pick whatever sounds happiest to you, and have fun reading the story.

For those who’d like a little more guidance, I’ve suggested a way to say each name in the character list. My suggestions do not match ancient pronunciation. They’re how I think the names will sound best in an English sentence.

THE ACTORS

Characters with an asterisk by their name were real historical people.

Nicolaos

NEE-CO-LAY-OS (Nicholas) Our Protagonist “I am Nicolaos son of Sophroniscus, of Athens.”

Socrates*

SOCK-RA-TEEZ An irritant “Will we get to see someone die?”

Diotima*

DIO-TEEMA A priestess of Artemis “Have you any idea how deadly it is in here?”

Timodemus*

TIM-O-DEEM-US (Timo) Athenian athlete, a friend of Nicolaos “This is embarrassing.”

Arakos

AR-AK-OS Spartan athlete He’s the big, silent type.

Markos

MARK-OS (Mark) A Spartan “We seem to have a problem here.”

Exelon

EX-EL-ON Chief of the Ten Judges of the Games “I blame Athens for this disaster.”

Pericles*

PERRY-CLEEZ A politician “Nicolaos, I want an Athenian victory. We need a victory.”

Gorgo*

GOR-GO The dowager Queen of Sparta “So you’re the ones they say are causing so much trouble.”

Klymene

KLY-MEN-EE Priestess of Demeter “I woke up, and there he was, naked.”

Pindar*

PIN-DAR A famous poet “I could teach you tricks of sycophancy that would make your eyes water.”

Pleistarchus*

PLY-STARK-OS King of Sparta “Why are you still alive?”

Festianos

FEST-EE-AHN-OS Uncle of Timodemus “I was a trifle worse the wear for drink.”

Niallos

NEAL-OS Team manager “I killed my friend.”

Timonous*

TIM-O-NOOS (One Eye) Father of Timodemus “A father is not always the most objective when it comes to his own son.”

Heraclides*

HERA-CLEED-EEZ A doctor “I’m a doctor. The idea is to not be with a corpse.”

Iphicles

IF-E-CLEEZ A charioteer “This is my lucky whip.”

Petale

PETAL-EE A hooker “I told you we girls were full up, so to speak.”

Pythax

PIE-THAX Chief of the city guard of Athens. Sports fan. “You look like you ain’t got a muscle in your body.”

Sophroniscus*

SOFF-RON-ISK-US Father of Nicolaos “Don’t add lying to your father to your crimes.”

Empedocles*

EMP-E-DOKE-LEEZ Philosopher “My plan is simple, yet brilliant. I was once a fish, you know.”

Libon*

LEE-BON An architect “The next three days will decide whether my life has been worthwhile.”

Xenia

ZEN-E-AH A slave “Are you hitting on me?”

The Fake Heracles A weakling “We do it for fun.”

Xenares

ZEN-AR-EEZ An ephor of Sparta “None of your wit, please. You can see this is a crisis.”

Aggelion, Megathenes & Korillos Athletes from Keos, Megara and Corinth “How can someone who doesn’t understand sport solve a sporting crime?”

Dromeus*

DRO-MAY-US An Olympic champion “Murdering don’t mean a thing, kid.”

The Chorus

Assorted athletes, judges, heralds, slaves, donkeys and crazed, drunken sports fans.

DAY 1 OF THE 80TH OLYMPIAD OF THE SACRED GAMES

THE PROCESSION WOUND past the Sanctuary of Zeus. They’d been walking two days, from Elis to Olympia.

“Will we get to see someone die?” Socrates asked. Like any boy, he looked forward to the violence of the struggle more than the beauty of the sport. Unlike me, Socrates had never seen death. To him, it was still a game.

“How should I know?” I said. “You can only hope.”

We stood in the crowd to watch the long line file past: the athletes, their fathers and uncles and brothers, the trainers, and the Ten Judges of the Games. Socrates jumped up and down to see over the shoulders of the spectators in front. That’s what he got for being a twelve-year-old in a crowd of mostly men.

The team from Sparta passed by, one of the few teams I could recognize without having to ask, because Spartans march in step where others walk. At the rear of the Spartans came one of the largest men I had ever seen, a towering hulk—he was half as tall again as me, with shoulders that could have hefted an ox. The chiton he wore had enough material to double as the sail for a small boat. The blacksmith who’d made his armor must have wept for joy at the challenge, then died of exhaustion trying to cover such a chest. Despite the two-day march, the large man’s stride was brisk; he looked neither left nor right, and he swung his well-muscled arms in much the same style as the Titans once had done when they strode the earth.

The Athenians came next. Leading them, almost in the shadow of the huge Spartan, was Timodemus, son of Timonous, of the deme Archarnae. I waved at once and shouted, “Chaire, Timodemus! Hail, Timodemus!”

He smiled broadly and waved back. “Chaire, Nicolaos!”

I raised my arms in a victory salute, meaning he

would win his event. Other men, all Athenians, cheered for Timodemus, too. Everyone knew he was one of the stars of this Olympics, a likely winner of the pankration, and Athens’s best hope of a victory.

The large Spartan, who had ignored everyone around him up to now, turned and said something to Timodemus. Timo’s smile disappeared in an instant. Perhaps the Spartan had complained of too much levity on what was supposed to be a solemn occasion.

Beside Timo walked a man who looked so like my friend I could have sworn the two were brothers, had I not known better. They were both short men and wore their hair cut almost to the scalp, but by his weathered skin and destroyed left eye, I knew the other to be Timo’s father. A third man, stockier and noticeably taller, walked with them a half-pace behind. He looked like an older brother, and one more tired by the long march. This could be no one but Timo’s uncle, and the eldest of the three. The men of Timo’s family were all former athletes, and though they were too old to compete, the father at least had kept himself in decent condition.

Timodemus and the rest of the Athenians were followed by the Corinthians, then the Thebans, the men of Argos and Thessaly, and Rhodes and all the other cities with athletes whose excellence permitted them to compete at the eightieth Games sacred to Zeus, king of the gods.

The last of the contestants passed by, the forlorn and grimy men from Megara, who every step of the way had eaten the dust raised by those who’d gone before. We spectators waited for the tail to pass, then followed as one large, milling crowd.

Though it was still early morning, already I sweated freely. The close mass of spectators added to the heat of this already hot midsummer day. There must have been ten thousand of us, from every part of Hellas, all at this one place called Olympia, here to bring glory to Zeus in the form of the greatest sport in the world.

We skirted the Sanctuary of Zeus, passed the newly raised temple—so new in fact I’d yet to look inside—and stopped at the Bouleterion, the council house of Olympia. Men elbowed one another for the best positions to see and hear the ceremony to come. Those at the back would struggle to hear. Socrates and I were small enough to weave our way toward the front.

The hellanodikai—the Judges of the Hellenes—took the steps up the Bouleterion. They were dressed in formal chitons of bright colors, with long sleeves that covered their arms and hems that went all the way down to their ankles. All ten wore expressions to match the gravity of their task. The judges were citizens of the city of Elis, within whose land Olympia lies. For the next five days, the word of these men was law, and no man, not Pericles nor a king of Sparta, could gainsay them. All were chosen for their honesty and integrity.

Before the council house stood a bronze statue of Zeus Herkios, who is Zeus of the Oaths. He was twice the height of any man, and he held in each hand a deadly thunderbolt, his right arm raised and ready to throw, a promise of retribution to any man who broke an oath made before him.

An enormous tripod stood to one side of the Zeus. It held aloft a wide brazier that had been polished till it gleamed and from which orange flames leaped up in a futile attempt to touch Apollo’s sun. I could feel the heat of the fire upon my face, even from a distance.

On the other side of Zeus lay a thick altar stone, where a boar squealed and struggled, its legs held down by two assistants whose chitons were soaked with sweat.

The Chief of the Judges stepped away from his fellows to stand before Zeus and address the crowd. He delivered a prayer—a loud one over the squeals of the waiting sacrifice—then recited the oath of the judges, in which he promised to be fair and honest in all his decisions, to take no bribes, and to respect the rules of the Games.

An assistant handed a knife to the Chief Judge, who took two steps to the writhing boar. He pushed back its head with his left hand to expose the neck to the sharp blade in his right. As he did, the animal twisted so much its hind legs came free; the body rotated and almost fell. The men swore, and their knees sagged under the weight as they struggled to prevent the squirming, screeching sacrifice from hitting the ground.

Men about me drew in their breath; if the animal escaped, it would be a disaster. The assistant who’d presented the knife jumped in and got his arms underneath at the last moment, and together they hauled the sacrifice back up. The Chief Judge didn’t wait for anything else to go wrong. He plunged his knife into the boar’s throat at once and sawed across the flesh. The blood spurted over everyone clustered about the altar. As sacrifices go, it had been as bad as you could get, but it was a death offered to Zeus, and that was the most important thing.

The crowd resumed breathing.

A man beside me said, “The sacrifice didn’t go willingly. It’s an ill omen.” Men around him nodded, and I could only agree.

“Not so,” said another man. “The boar struggled to live as the competitors will struggle to win. Zeus favors us with a tough contest this Olympiad.” It was a middle-aged man who spoke, and balding, but his voice held authority and a melodious tone that carried well. Many heard him, and the crowd settled at his words.

The way the man had controlled us with his voice reminded me of Pericles. Curious, I studied this stranger from aside. He had the look of a priest about him. But no priest I’d ever seen had such a piercing way with his eyes or such intensity of expression. His head turned at that moment, and our eyes locked. He must have known I’d been staring, but he didn’t seem upset so much as resigned, as if he was used to such rudeness. I was embarrassed and turned back to the action before I felt forced to say something.

The Butcher of the Games stepped forward with his meat cleaver. He dismembered the thighs of the still-quivering boar and cut the meat into thin slices. The Chief Judge took the first slice, and with bloody fingers tossed it into the brazier, where the offering could be heard to sizzle as the meat roasted to charcoal. They were not cooking the flesh but giving it to Zeus, because meat on which an oath has been made may not be eaten by mortal man.

Each Judge in his turn repeated the actions of the Chief until all ten had made their oaths and reinforced them with the blood and meat of the sacrifice.

Next it was the turn of the athletes. They stepped forward, one by one, and made their oath—a different one than that of the judges—to obey the rules, to neither cheat nor bribe, and in addition they swore they had trained for at least ten months. To the men who would compete in the boxing and the pankration, after each made his oath, the Chief Judge added, “Mighty Zeus absolves you, athlete, from the charge of murder if you kill your opponent in the contest.” Each athlete to whom the Chief Judge said this thanked him and stepped away.

The trainers and the fathers, brothers, and uncles of the athletes, too, were required to make their oaths, but without the need to affirm they had trained. For them, the oath was required merely to ensure they did not cheat in favor of their relative.

As they waited their turn in line, I saw the Spartan turn once more to Timodemus and say something. It must have been an insult, because Timo scowled and started forward. As one, Timo’s father and uncle grabbed Timodemus by the shoulders and dragged him back. The Spartan laughed and turned his back on them.

Timo’s father spoke to Timo, and even at a distance I could see they were harsh words. He’d probably ordered Timo not to let the man provoke him. What was going on? It was an act of utmost arrogance for the Spartan to insult a man and then expose his back.

I nudged the man next to me. “The big man to the side over there, the one among the Spartans. Do you know who he is?”

He looked where I pointed and nodded. “That’s Arakos. He fights for the Spartans in the pankration. They say to face him is like fighting a rock.”

The pankration was Timo’s own event.

Dear Gods, Timo would have to fight that monster? Timo was a dead man.

Arakos the Spartan stepped forward to take his turn at the altar, along with his trainer but no father or family. Arakos made his oath, and the Chief Judge absolved him of murder in the c

oming contest.

Then it was Timo’s turn to take the oath, to promise not to cheat, and to sacrifice a thin slice of the boar.

Arakos of Sparta spoke once more as Timodemus came down the steps. Timodemus froze, then snarled in rage. Every man present heard that snarl. Every head snapped in their direction. My friend Timodemus, in full view of the judges and the crowd, launched himself off the steps, hands stretching to strangle the Spartan.

THE FIRST EVENT of the Olympics is always the competition for the heralds. It begins straight after the opening ceremony. Each contestant in turn stands in the Colonnade of the Echoes—a narrow passage lined with columns—where he makes a practice announcement that echoes back and forth seven times. The judges decide which hopefuls have the loudest, clearest voices, and they become the Heralds of the Games, their job to start each event and announce the winners.

I didn’t need to hear a lot of men shout at the tops of their voices. If I wanted to be shouted at, all I had to do was find my father; he was with his friends somewhere in this crowd.

This was my first Olympics. Father had always refused to take us when I was a child. He had no interest in sport, only in sculpture. Yet all of a sudden, he’d taken an interest in the Games. I wondered why but not enough to risk the question. It seemed every time Sophroniscus and I spoke these days, it turned into an argument.

So instead I went in search of my friend Timodemus, who’d been dragged off the Spartan and led away by his trainer and his father in utmost disgrace. They might have taken him to the temple to sacrifice and pray to Zeus—for surely Timo had breached his oath the moment he’d spoken it, when he attacked another competitor—or perhaps they’d taken him to the river to throw him in to cool down, or back to the Athenian camp where he’d be safe from angry Spartan fans, or to the temporary gymnasium reserved for the athletes.

He wasn’t at the temple, which surprised me a little. If I were in his position, I’d have been praying as hard as I could, because Zeus is not a forgiving God, and the thunderbolts in his hands are hard to forget. Instead I found Timo, with his father and uncle and trainer, at the second place I looked: the gymnasium. When I walked in and saw them there, I was taken aback for a moment. Some men might have thought it a trifle callous, or at least arrogant, to repair to the revered place of athletes straight after such an unsportsmanlike incident.

The Singer from Memphis

The Singer from Memphis Death on Delos

Death on Delos Sacred Games

Sacred Games The Ionia Sanction

The Ionia Sanction Death Ex Machina

Death Ex Machina The Pericles Commission

The Pericles Commission